VARIOUS

Recently I had occasion to walk through a toy department in one of our largest retailers. Very interesting. Toys sure have changed since my little kid days. Some of the stuff looked interesting and imaginative, but too much of it, way too much, seemed to reflect a warped imagination, a distorted view of reality, a proneness to entice our most superficial energies, a programming of the young mind for total unreality. Things do not bode well for our future! Of course all this prepares them quite well for our unreal techno world.

I ran across this quote from Charlotte Joko Beck, a Zen teacher: “We’re here to get our present model repainted a little bit. If the car of our life is a deep grey, we want to turn it into lavender or pink. But transformation means that the car may disappear altogether. Maybe instead of a car it will be a turtle. We don’t even want to hear of such possibilities. We hope that the teacher will tell us something that will fix our present model. A lot of therapy merely provides techniques for improving the model. They tinker here and there, and we may even feel a lot better. Still, that is not transformation. Transformation arises from a willingness that develops very slowly over time to be what life asks of us. Most of us (myself included at times) are like children: we want something or somebody to give us what a small child wants from its parents. We want to be given peace, attention, comfort, understanding. If our life doesn’t give us this, we think, ‘A few years of Zen practice will do this for me.’ No, they won’t. That’s not what practice is about. Practice is about opening ourselves so that this little ‘I’ that wants and wants and wants and wants and wants–that wants the whole world to be its parents, really–grows up.”

Indeed. Well put! In addition to what she is saying here directly, this also has a certain relevence and application to people entering monastic life. Very often they come to monastic life just to get their “present model repainted a little bit.” When it turns out that the life is pulling them into something much more demanding, a lot of them bail out. Another interesting application of this account is to the public sphere, the social and political reality. This extrapolation I will leave to you.

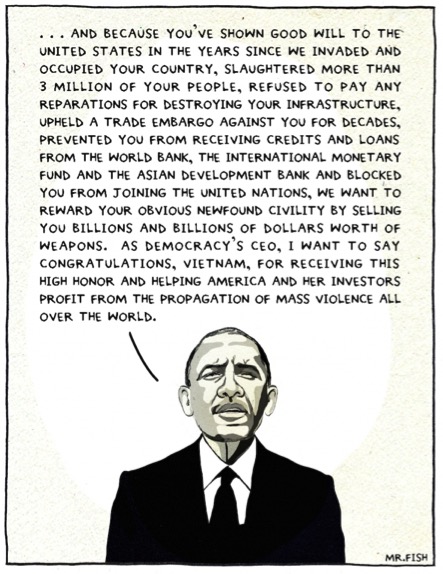

Speaking of politics, we are approaching a very critical national election. An election that has enormous moral and religious dimensions as well as social and economic ones. More is at stake in this election than at any time since I think the LBJ–Goldwater tussle back in 1964. As much as I dislike and distrust Hillary Clinton as a politician and as much as I think that there are many questions around her, it is absolutely imperative that Trump be defeated for the sake of the common good and the well-being of the nation. And it does seem as I write this that Clinton should have a very sizeable victory. But….and this is a BIG “but”….I won’t be celebrating the day after election day. This is not only because of my view of Clinton, but much more so because I realize that Trump is not “the disease”; he is only one symptom of what ails America now. And this problem is going to be with us after election day big time!

Random Thoughts On Politics:

The Economist, hardly a leftist rag, recently had an article with the title, “The Debasing of American Politics.” Just one sentence tells you what that’s about: “By normalizing attitudes that, before he came along, were publicly taboo, Mr. Trump has taken a knuckle-duster to American political culture.” Indeed. So true, but note the key words–“publicly taboo.” Trump is only bringing to the surface and to the light what was lurking there all along, things that were “not allowed” to appear in the public sphere.

Sometimes I wonder…. I recall a Scripture scholar I had in seminary, an elderly Jesuit who was the essence of gentleness and kindness and deeply knowledgeable in all the ancient languages. I never really enjoyed Scripture classes as a rule–they seemed to me to kill the spiritual element there–but this guy was interesting to listen to. One day, however, he jolted me out of my complacency. He pointed to something in the Gospel of Luke that was right there in front of my nose but which we all usually just take for granted, never really pondering the full implications of these words. The full pericope was the “Temptation in the Desert,” Lk 4: 5-7—“Then the devil led him up and showed him in an instant all the kingdoms of the world. And the devil said to him, ‘To you I will give their glory and all this authority; for it has been given over to me, and I give it to anyone I please.’” (Similar words in Matthew.) The old Jesuit was trying to challenge all the young Jesuit students in class (I was the only non-Jesuit in class!) who at that time were totally mesmerized by the call to political action as a religious activity, and you can readily understand that in the context of Liberation theology and other such movements. The old Jesuit was simply cautioning them not to “put all their chips” on politics. This realm is not a “godly realm” no matter how good your intentions; and if you really study history you will begin to see what he means. Well, at that time I thought he was overly pessimistic, and I still do today; but, sometimes, I begin to wonder…..

American history is an eye-opener if you get beyond the mythologized narrative they give you in school. Read Howard Zinn’s account for a change. In any case, just as an example, I used to idolize Thomas Jefferson. I even identified myself as a “Jeffersonian American”—until I discovered the “real” Jefferson, the one who not only was a slave-owner but also participated energetically in hunting down runaway slaves, dead or alive. On top of that, when he became president and got that big piece of land from the French, the Louisiana Purchase, he planned the removal or extermination of all natives from that land. This is the guy who wrote the Declaration of Independence and “all men are created equal.” In school we usually get only half the picture. Or take the case of the Democrat Woodrow Wilson who had the support of the KKK and welcomed that support and wanted to keep Blacks “in their place,” and lied to get us into World War I so that many made money off that–like the Republican George Bush in recent years. So the story goes…..

All through American history the political parties and the candidates they put forward are only “beards” for various money interests. The term “beard” comes from the world of sports betting. When a person cannot or does not want to be seen making a big sports bet in a casino, he will send in another person to make that bet for him. The bet’s true owner is thus concealed, and the person making this bet is called a “beard.” The image is self-explanatory! In any case, the phenomenon can be seen in politics quite readily.

One of the really serious problems in American politics is the truncated nature of our choices. Ok, the Republicans are really a far right party; and the Dems are more a center-right party, to use a European metric. To use the word “leftist” for the Dems is to not see what is really going on. Even the much weaker word “liberal” will not do–primarily because it has had so many different changes in meaning over the last century. If another serious choice pops up, like the socialist Bernie Sanders, he has to run as a Dem to have any chance and then the system will find a way to defeat him. I followed the Washington Post’s handling of the Sanders campaign and it was amazingly negative, even making fun and distorting all his proposals and his agenda. What we have really is what Chomsky called “a manufactured consent.” Only these two options will be allowed. And one is getting so looney that pretty soon we might really have only a one-party system.

I saw in the news an evangelical Trump supporter holding a Bible in one hand and a rifle in another. No more need be said. Then, again, I am totally perturbed, even aghast, that Trump is doing relatively well among my own Catholic community. Granted, these are conservative Catholics, but don’t they know anything about Catholic social teaching? It will be interesting to see what the demographics of the Trump support will be on Election Day. How many vote for him and exactly who votes for him. I predict that he will get about 38% of the vote, which is truly bad for the country considering there are THAT many people who believe in Trump. They will be there after the election as a real problem. If Trump gets over 40%, we are in BIG trouble; and if he gets around 48%, I am getting in touch with the Canadian embassy!

So what has happened to the Republican Party? Way back when, it used to stand against American involvement in foreign wars and supported civil rights, more or less. The party of Robert Taft, Eisenhower and Rockefeller, you could have an honest debate with. Trump’s supporters today talk of rebellion and assassination if they lose the election. Even Richard Nixon, wow I can’t believe I am saying this, had some remarkable positions but all these went down the toilet of history with Watergate. Few people know that he was responsible for starting the Environmental Protection Agency and for getting the Clean Air and Pure Water Act passed. He was also going to push for a single-payer health plan in the U.S. way back in 1970; and he was also exploring the feasibility of a guaranteed income for all American citizens, whether they worked or not, something that is only now being tried in Finland. Even Bernie didn’t openly propose that! What happened since Reagan is a complex phenomenon but it can be reduced to several elements at least. One is a real deep anger and frustration that a lot of people are feeling that demagogues like Trump and the far right have exploited to the nth-degree. This anger is due both to constant propagandizing and distorting by the far-right and it is due to a perceived betrayal by the elites of the country. And so any “anti-establishment” voice will get a hearing in this climate. Both Sanders and Trump actually connected to some of that, but one totally exploited that anger and anxiety ; the other tried to address it to some extent. Interesting that Bernie Sanders, this very old Jewish figure, gave voice to so much of Catholic Social Teaching (unbeknownst to him!!) and appealed to an overwhelming majority of people under 30…..the future.

About the future of the Republican Party…..recently Mother Jones had an interesting article about a Republican senator from Nebraska, Ben Sasse. An obviously intelligent man, a Ph.D. in history from Yale, an evangelical, and someone who was critical of Trump from the very beginning and disassociated himself from “Trumpism.” That much he is to be commended for, and perhaps he can be a building block for a new Republican Party of the future. However, Sasse sees the problems of Trump as a “personal behavior” problem ,more or less, and he is objectionable as a person. I think that is only scratching the surface. Sasse himself seems to be part of that very wave that Trump is riding….the Tea Party. And with support from Sarah Palin and Ted Cruz, he is not in good company. But we shall see…. As Mother Jones implies at the end, we have yet to see the real Sasse and what he stands for. He uses terms like “entitlement reform” and he says he is against “centralized planning,” for example, and these kind of words usually lead to privatizing Social Security, cutting Medicare and the likes. What Sasse really needs is a really different Republican vision, and for that we will have to wait and see. Right now they are starting to spew this “the-election-is-rigged” thing, and they are preparing to be total obstructionists for Clinton just as they were for Obama. Obama’s big mistake was his inclination to try and “work together” with these folks, not really assessing their nasty intentions. LBJ used to pull Republican congressman to the White House and tell them that he would pull all Federal money out of their district if they didn’t vote for such and such a bill. That’s how he got the Civil Rights Act passed and the War on Poverty. It’s not “nice” but when you are faced with that degree of nastiness and so much is at stake, then you better be tough enough to twist some political arms, that is, if you really want to get such legislation passed. That’s a whole other story. In any case, it remains to be seen if Sasse will be with these obstructionists or will he try to lead another kind of Republican “loyal opposition” that will actually dialogue and compromise with Clinton. A lot is at stake in all this for the well-being of the country.

A much deeper survey of our situation is hinted at in this incredibly complex essay by Henry A. Giroux. As Giroux acutely observes, our problems are a lot more serious than this or that politician. Here is the beginning of this piece verbatim:

“What happens to a society when thinking is eviscerated and is disdained in favor of raw emotion? What happens when political discourse functions as a bunker rather than a bridge? What happens when the spheres of morality and spirituality give way to the naked instrumentalism of a savage market rationality? What happens when time becomes a burden for most people and surviving becomes more crucial than trying to lead a life with dignity? What happens when domestic terrorism, disposability, and social death become the new signposts and defining features of a society? What happens to a social order ruled by an “economics of contempt” that blames the poor for their condition and wallows in a culture of shaming? What happens when loneliness and isolation become the preferred modes of sociality? What happens to a polity when it retreats into private silos and is no longer able to connect personal suffering with larger social issues? What happens to thinking when a society is addicted to speed and over-stimulation? What happens to a country when the presiding principles of a society are violence and ignorance? What happens is that democracy withers not just as an ideal but also as a reality, and individual and social agency become weaponized as part of the larger spectacle and matrix of violence.

The forces normalizing and contributing to such violence are too expansive to cite, but surely they would include: the absurdity of celebrity culture; the blight of rampant consumerism; state-legitimated pedagogies of repression that kill the imagination of students; a culture of immediacy in which accelerated time leaves no room for reflection; the reduction of education to training; the transformation of mainstream media into a mix of advertisements, propaganda, and entertainment; the emergence of an economic system which argues that only the market can provide remedies for the endless problems it produces, extending from massive poverty and unemployment to decaying schools and a war on poor minority youth; the expanding use of state secrecy and the fear-producing surveillance state; and a Hollywood fluff machine that rarely relies on anything but an endless spectacle of mind-numbing violence. Historical memory has been reduced to the likes of a Disney theme park and a culture of instant gratification has a lock on producing new levels of social amnesia.”

Here is the link to this article:

http://www.counterpunch.org/2016/09/30/thinking-dangerously-in-the-age-of-normalized-ignorance/

Christ Hedges, my favorite commentator writes about Trump—“Donald Trump: The Dress Rehearsal For Fascism” Here is the link:

http://www.truthdig.com/report/item/donald_trump_the_dress_rehearsal_for_fascism_20161016

And a more mainstream commentator, Robert Reich, who once served in the Clinton Cabinet and is now a professor at Berkeley, has an alarming prognostication–that a win by Hillary will be welcome by Wall Street and that they will get something important for them from her and the growing income disparity will continue to widen. Here is the link to that piece:

The things these folks predict may not happen, but still we need to face our predicament with open eyes and with thoughtful minds and hearts. The future is going to be a most serious challenge.

Leaving this quagmire of politics, now I would like to turn to a very different kind of person and a very different kind of world: In The Sun Magazine there recently was this article: “Not On Any Map: Jack Turner On Our Lost Intimacy With the Natural World,” by Leath Tonino. It is a marvelous interview with Mr. Turner and here is the introduction to this piece:

“ Since 1978 he has lived at the foot of the Tetons, one of North America’s most dramatic mountain ranges, usually in cabins without electricity or running water. A retired mountain guide, he believes that to really love a place, one must forge an intimate, bodily relationship with it, and that to do so in this day and age is an “achievement.” One cabin in which he lived, a twelve-by-twenty-foot plywood shack located inside Grand Teton National Park, could be reached during the winter months only by skiing or snowshoeing four miles from the nearest plowed road. Temperatures sometimes dropped to 40 below. Weeks passed without a visit to town. He says the years he spent there with his wife, Dana, and dog, Rio, were the best of his life.

Raised in Washington, D.C., and Southern California, Turner grew up in a family of outdoorsmen. His grandfather was the co-owner of a hunting-and-fishing camp in northern Pennsylvania, and his father hunted and fished year-round. Turner got an undergraduate degree in philosophy at the University of Colorado and went on to study Chinese and philosophy at Stanford and Cornell. Soon after, he accepted a teaching position at the University of Illinois in Chicago, but he was less comfortable in the halls of academia than he was wandering the backcountry. He’d become obsessed with rock climbing in the early 1960s, and by the middle of that decade he was partnering with some of the best climbers in the U.S. on difficult routes in Yosemite National Park and Colorado. He loved climbing more than philosophy, so he quit being a professor. The mountains were calling, and he trusted their voice.

Now seventy-two years old, Turner has spent more time outdoors in pursuit of wildness and wilderness than anybody else you’re likely to meet. For forty-two years he worked for Exum Mountain Guides, a company based in Wyoming, leading clients up the 13,776-foot Grand Teton and neighboring peaks. He has climbed the Grand Teton roughly four hundred times and participated in more than forty treks and expeditions to Pakistan, India, China, Tibet, Nepal, Bhutan, and Peru. In his free time he’s backpacked, canoed, fished, bird-watched, and camped — often alone and always without a GPS — all across North America.”

Now this guy I really feel in tune with! He makes a very strong case for the human need for real and personal encounter with wilderness for both human and spiritual health. This is a topic that I have touched on a few times in this blog, and I was exhilarated by this interview. He also has a good understanding of the hermit life, which is quite rare. Here is the link to the full online interview:

http://thesunmagazine.org/issues/464/not_on_any_map

And let us conclude with an actual contemporary Zen story. This took place at Esalen, the New Age spirituality and therapy center right on the coast of California in Big Sur and just down the road from the Hermitage where I lived at the time. Kobun Chino Roshi, who was a Zen master and a master of Kyudo, the way of the bow, was visiting Esalen with his archery teacher. The teacher fired off some arrows at a practice target and then he handed off the bow and arrow to Kobun and invited him to demonstrate his skill. Esalen is high on a cliff overlooking the Pacific. Kobun took an arrow and with complete concentration and attention and care shot the arrow into the ocean. When it hit the water he said, “Bull’s eye!” (The story is told in Essential Zen.)

This is connected to everything I wrote above, but don’t ask for an explanation!!