- We are coming near the anniversary of Merton’s death in December of 1968. It is hard to believe that this tragic event took place 46 years ago! Merton was only in his early 50s–to think what he would have written after his Asian trip….if he had only lived at least into his 60s like Abhishiktananda…. Sad too that he never met Abhishiktananda when he was in India. The two men were very different in some significant ways and had some very different interests–Merton was ranging far and wide with his interests in the Sufis and Buddhism and Christian monastic sources and social movements–not very much interest in Hinduism, showed little penetration of the Upanishads; while Abhishiktananda focused almost exclusively on his India and Hinduism and even there almost exclusively on the Advaita of the Upanishads–ignoring the very real dualistic schools of India. But I think the meeting would have been something exceptional.

- Some of Merton’s writings seem now a bit dated; others are not only still very relevant but truly prophetic pointing us to a future not yet realized. Also in light of Abhishiktananda’s journey and explorations, Merton’s seems more cautious, more conservative, not so much “pushing the theological envelope.” But in his encounter with Tibetan Buddhism I think he turned a certain corner, and you wonder where he was headed for….! I think his main contributions can be summed up as: a.) focusing us on the contemplative and mystical dimension of Christianity and Christian monastic life (as opposed to a simple institutional “belonging” or some exercise in piety and morality); b.)showing the deep connections between the contemplative and social concerns; c.) helping bring back the whole hermit tradition in Christianity; and d.) opening to the great world religions and willingness to learn from them.

- In his Asian Journal Merton relates this encounter with a Tibetan Lama:

“The Khempo of Namgyal deflected a question of mine about metaphysics…by saying that the real ground of his Gelugpa study and practice was the knowledge of suffering, and that only when a person was fully convinced of the immensity of suffering and its complete universality and saw the need of deliverance from it, and sought deliverance for all beings, could he begin to understand sunyata…. When one read the Prajnaparamita on suffering and was thoroughly moved, ‘so that the hairs of the body stood on end,’ one was ready for meditation–called to it–and indeed to further study.”

- As is well known Merton was very much attracted to Tibetan Buddhism once he was exposed to it. Tibetan Buddhism is a very beautiful and profound religious path and currently a very vital tradition with many true practitioners (one can’t say the same about Chinese Zen or Japanese Zen at this time). However, I think it has one “weakness” which keeps some from fully engaging with it and it earns it a kind of superficial mystique that distracts from its real truth: its enormous complexity and the manifold and systematic elaborations. On the one hand this leads to an atmosphere of “esoterica” and hidden knowledge; on the other there is that feeling that one is climbing this endless mountain with endless steps on the way “up.” A lot of this has been demystified by the Dalai Lama and other deep practitioners–without taking away the truly laborious nature of the path–they point to the basic goal: utter selflessness, unspeakable compassion, an unfettered view of the world, true peace, etc. The ultimate goal of Tibetan Buddhism is really utterly and unspeakably simple(just as in every major spiritual tradition, the Ultimate Reality is always Absolutely Simple)–so simple that in fact paradoxically the “way there” can seem very complex. Merton handled the complexities of Tibetan Buddhism in an interesting way. He had this incredible gift for peeling away the secondary and tertiary matters to get to the “essence” or the heart of the matter at hand. In his conversations with some of the lamas when they talked of mandalas or something downright exotic, etc., he would note it down in his notebook later on but then he would add something like, “That’s not for me;” or “I don’t think I need that.” I don’t know how that would have worked out in the long run, whether he could have really gotten to the core of Tibetan Buddhist meditation–this is what he was most interested in–not any theological or philosophical speculation, whether he could have done that without that elaborate apparatus, we will never know.

- On their part the lamas also had an interesting response to Merton. Most of them could see that he was an “accomplished meditator,” not the usual Westerner that approached them. Both from his discourse, the questions he asked, and from his presence they could tell he was a deep person spiritually, although they were surprised that was possible for a Christian!! Mostly Christianity was seen as an external, institutional religion (which by the way the Dalai Lama very much respects). Recall his meeting with Chatral Rimpoche, the lama he deeply connected with (in addition to the Dalai Lama). Here is Merton in his own words:

“We started talking about dzogchen and Nyingmapa meditation and ‘direct realization’ and soon saw that we agreed very well. We must have talked for two hours or more covering all sorts of ground, mostly around the idea of dzogchen, but also taking in some points of Christian doctrine compared with Buddhist: dharmakaya…the Risen Christ, suffering, compassion for all creatures, motives for ‘helping others,’–but all leading back to dzogchen, the ultimate emptiness, the unity of sunyata and karuna, going ‘beyond the dharmakaya’ and ‘beyond God’ to the ultimate perfect emptiness. He said that he had meditated in solitude for thirty years or more and had not attained to perfect emptiness and I said I hadn’t either. The unspoken or half-spoken message of the talk was our complete understanding of each other as people who were somehow on the edge of great realization and knew it and were trying, somehow or other, to go out and get lost in it–and that it was a grace for us to meet one another. He burst out and called me a rangjung Sangay (which apparently means a ‘natural Buddha’)…. He told me seriously that perhaps he and I would attain to complete Buddhahood in our next lives, perhaps even in this life, and the parting note was a kind of compact that we would both do our best to make it in this life. I was profoundly moved, because he is so obviously a great man, the true practitioner of dzogchen, the best of the Nyingmapa lamas, marked by complete simplicity and freedom. He was surprised at getting on so well with a Christian and at one point laughed and said, ‘There must be something wrong here!’”

- No one know where Merton would have ended up, both physically and spiritually. After India and Bangkok there were plans to go and visit some Zen masters in Japan and then a little -known venture was planned to go and visit some Sufis in Iran, before returning through Europe to Gethsemani. One wonders where he would have settled after that. My guess is that he would have tried to live as a hermit at Redwoods where many would have come to see him. No matter where he went, there would have been a crowd! And I think he needed that in spite of his search for “more solitude.” He really flourished when he was interacting with other spiritual seekers.

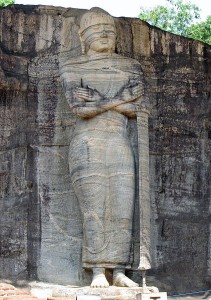

- Let us conclude with another quote from the Asian Journal, among his last words, from that famous “enlightenment moment” before the great Buddha statues. These are also among his most beautiful words:

“I am able to approach the Buddhas barefoot and undisturbed, my feet in wet grass, wet sand. Then the silence of the extraordinary faces. The great smiles. Huge and yet subtle. Filled with every possibility, questioning nothing, knowing everything , rejecting nothing, the peace not of emotional resignation but of Madhyamika, of sunyata, that has seen through every question without trying to discredit anyone or anything–without refutation–without establishing some other argument. For the doctrinaire, the mind that needs well-established positions, such peace, such silence, can be frightening. I was knocked over with a rush of relief and thankfulness at the obvious clarity of the figures, the clarity and fluidity of shape and line, the design of the monumental bodies composed into the rock shape and landscape, figure, rock, and tree…. Looking at these figures I was suddenly, almost forcibly, jerked clean out of the habitual, half-tied vision of things, and an inner clearness, clarity as if exploding from the rocks themselves, became evident and obvious. … The thing about all this is that there is no puzzle, no problem, and really no ‘mystery.’ All problems are resolved and everything is clear, simply because what matters is clear. The rock, all matter, is charged with dharmakaya…everything is emptiness and everything is compassion. I don’t know when in my life I have ever had such a sense of beauty and spiritual validity running together in one aesthetic illumination. Surely with Mahabalipuram and Polonnaruwa my Asian pilgrimage has come clear and purified itself. I mean, I know and have seen what I was obscurely looking for. I don’t know what else remains but I have now seen and have pierced through the surface and have got beyond the shadow and the disguise. This is Asia in its purity, not covered over with garbage, Asian or European or American, and it is clear, pure, complete. It says everything ; it needs nothing. And because it needs nothing it can afford to be silent, unnoticed, undiscovered. It does not need to be discovered. It is we, Asians included, who need to discover it.”

Good words to end with. Good words to begin with.