Striking how the word “no” plays such a prominent role on the spiritual journey. Did you know that the critical step in any serious spirituality is to “be nobody”? Yup, that’s a fact! But it’s not to be confused with the “no” of popular religiosity or pop social living. You know, the Lent sort of thing, “no candy,” “no sex,” “no talking,” ”no this,” “no that,” etc. Some of these “no’s” are important for healthy living, some are not, and many are just a kind of “traffic control.” But the fundamental “no” of the spiritual journey has a vastly different resonance. This one has to do with our fundamental identity, and despite its negative appearance and similarity with negation it is in fact the most positive affirmation we can make.

Recall that old move from the ‘50s, “On the Waterfront,” with Marlon Brando. At one point in the story the Brando character, a boxer, is angrily lamenting to his brother, who betrayed him and induced him to throw a fight, “I could’ve been a contender. I could’ve been somebody.” In a sense this is the universal human anguish, “to be somebody.” We all have this built-in tendency to grasp at this “somebody” in our dreams and desires and realities around us. We are utterly afraid of having no name, no title, no credentials of any kind–like undocumented immigrants: “no papers”! Consumerism is another dynamic in this attempt to be “somebody”–I consume/shop; therefore I am! Even religious people, and maybe especially religious people, have a tendency to get lost in this quagmire of unreality and images and shadows because when there is a “religious name” on this “somebody” it seems to be more real, more substantial, etc. Ah, the importance of having a certain name or designation!

Recently I came across a book with the engaging title, Be Nobody, written by someone I never heard of before, Lama Marut. It is a kind of “New Age” spirituality thing and mostly I stay away from that stuff, but this book actually has a lot of solid and helpful insights and overall a good reminder of what I am mentioning above. The author mystifies me–grew up as a conservative Baptist, became a professor of comparative religions, specializing in Hinduism, then dropped that and became a Tibetan Buddhist monk, now he no longer is a monk but writes and teaches “spirituality.” It puzzles me why he keeps that name, Lama Marut, and I only mention it because he seems to illustrate the very problem he writes about: that need to be “somebody.” If he were still deeply connected to Tibetan Buddhism and had gotten that title through an authentic transmission, well, then that would be understandable. But now it would seem that his book could have been written by “Joe Blow” and it would be more truthful in a sense to have some kind of “plain name.” No matter; the book has some good things to say, and in the spirit of Jesus, wherever we find goodness and truth we should acknowledge it and learn from it.

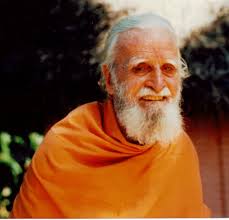

I called the work “New Age spirituality”–it’s not as weird or flakey or superficial as a lot of that stuff is, but it shares one very important characteristic of the New Age movement: it is spirituality disconnected from any tradition or religion. Yes, it borrows and uses elements from a lot of different traditions but there is no fundamental commitment to any one tradition. In fact Lama Marut makes a big point about that, about a need for a spirituality abstracted from all religions but drawing on them all. From the Preface: “The point is not to be a Buddhist but to learn how to become a Buddha; not just to identify with the label ‘Christian’ but to live a Christlike life; not simply to join a religion as a way to strengthen one’s sense of self but to actually live a good life, a life characterized by egoless concern for others.” One can see what he is getting at and largely agree with it as far as it goes, but the actual situation is a bit more complex. It may be that being committed to a tradition, belonging to a Church, etc., will keep one on a serious path and avoid simply dabbling in spirituality. It is this which must be avoided by all means and without that anchor and the wisdom passed down through countless wise holy people in each tradition, you wonder if a person might not get lost in a lot of superficial stuff. Also at a certain point one has to “give up one’s life” if one is serious on a path, and I am not sure that a self-constructed spirituality will help you through that tunnel! But, on the other hand, I am very sympathetic to spiritual seekers who are “traditionless,” “churchless,” even “religionless”–I think there are situations and people for whom that is the only viable path. Here is another quote from that book–here he is quoting Swami Satchidananda, who became a favorite guru of many New Agers: “People often ask me, ‘What religion are you? You talk about the Bible, Koran, Torah. Are you a Hindu?’ I say, ‘I am not a Catholic, a Buddhist, or a Hindu, but an Undo. My religion is Undoism. We have done enough damage. We have to stop doing any more and simply undo the damage we have already done.’” I can fully sympathize with that position, even applaud it, but I think one may be able to “undo” a lot more by staying within one’s tradition.

Enough about all this and let’s get back to our main topic and here this little book has some good contributions:

- The book has a good handle on one of the most important questions of the spiritual journey: who am I? The problem of identity. The call to be “Nobody” is not a negative thing but an affirmation of an identity much deeper than any social/psychological construction. From the book: “’Nobody,’ as we use the term here, refers to our deepest nature, our ‘true self,’ which is ever-present and in no need of improvement. It is our highest source of joy and strength, the eternal reservoir of peace and contentment to which we repair in order to silence the persistent demands and complaints of the insatiable ego. Letting go of our preoccupation with being important and significant will not be easy. Laboring at being somebody for so long digs deep ruts of habit, and some ingrained part of us will surely resist the required ‘ego-ectomy.’ But there’s a great relief in dropping the ego’s restrictive inhibitions and demands for affirmation and magnification…. With the rise and vapidity of social networking and ‘reality’ television, the veneration of the ego, celebrity, and instant fame, and the closed-minded arrogance of religious fundamentalism…the questions revolving around the nexus of spirituality and identity have never been more pressing….”

- The book does a good job of presenting a summary of the social background and cultural critique that was emerging in recent decades around the issue of our sense of self. Journalist Tom Wolfe called the early ‘70s the “Me Decade,” and in 1979 Christopher Lasch wrote The Culture of Narcissism, a scathing critique of the narcissistic preoccupation with the self at the cultural/social level. Today we live in the “iERA”(as in iPad!).

- The book does a good job at distinguishing this “Nobody” we seek from the kind of psychological afflictions people experience: poor self-image, feelings of worthlessness, self-hatred and self-rejection.

- A number of excellent quotes in the book, but the key one for us is this one from Merton: “There is an irreducible opposition between the deep transcendent self that awakens only in contemplation and the superficial, external self that we commonly identify with the first person singular. We must remember that this superficial ‘I’ is not our real self. It is our ‘individuality’ and our ‘empirical self,’ but it is not truly the hidden and mysterious person in whom we subsist before the eyes of God. The ‘I’ that works in the world, thinks about itself, observes its own reactions, and talks about itself is not the true ‘I’ that has been united to God in Christ.”

- I liked this insight and this shows Lama Marut’s Buddhist training: “…the interminable pursuit of being somebody can become a heavy load to carry. If, for example, we believe that our “specialness” derives from what we have achieved rather than from who we really are, we will be forever striving to be important enough, famous enough, rich enough, loved enough, accomplished enough…. If we fully buy into an accomplishment-based understanding of selfhood, we’ll be perpetually trying, and endlessly failing, to be somebody enough. When we wholly identify with one or another of the roles we play in the ongoing drama that is life, we may begin to suspect that no matter how successful we are–no matter how many promotions we win, how much money we accumulate, how much praise we receive –it will never be sufficient.”

This is called “dukkha” in Buddhism, often translated as “suffering.”

Think of the Christian Desert Fathers, the founders of Christian monasticism, they knew this kind of thing in their own language if you can translate it into our modern terms–over the years Catholic religious discourse and even Orthodox spiritual writers have overlaid a kind of masochistic piety on the stories and language of these giants of the Desert. In fact the Desert Fathers (and Mothers) had one word that perfectly summed up the whole enterprise of discovering your true self as Nobody: humility–the most important word and value in the Desert. That word was so cheapened and eviscerated over the years that its profundity and scope got lost in a maze of superficial “spiritual” attitudes.

But think also of the New Testament. Here Lama Marut quotes C. S. Lewis (hardly a New Age figure!): “The terrible thing, the almost impossible thing is to hand over your whole self–all your wishes and precautions–to Christ. But it is far easier than what we are all trying to do instead. For what we are trying to do is to remain what we call ‘ourselves’….” And consider this from the Gospel (Mt. 11: 28-30): “Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me; for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light.” Consider now the Greek myth of Sisyphus, where Sisyphus is condemned to Greek hell where he has the task of rolling this stone up a steep hill and the stone gets heavier and heavier as he gets toward the top until it becomes too heavy for him and it rolls down to the bottom and he has to start all over. Alas, that is the iconic picture of the heavy burden of our ego self and all our efforts at building it up, enhancing it, satisfying its insatiable needs, etc. The heaviest burden we have to carry is precisely our ego self, and the amazing thing is that this seems “normal,” “the accepted thing,” “the way things are,”…. All the major spiritual/mystic traditions of the world have a way of “unburdening” us and in a sense they all generally point in the same direction. But in Christianity we express it through this reality of our oneness with Christ and in Christ. We “put on the mind of Christ,” we become Christlike, we live now, “not I, but Christ lives in me,” and so on. This Nobody we truly are is our real self in a nondual union with Christ and lost in God. To live from that sense of identity is to live literally without any burden in pure bliss and total freedom and unlimited compassion.

- One last idea from the book: “The lower, individual self is an idea of the self, but our self- conception is constantly in flux. This self, we could say, is a process, not a thing. To invoke a very common and ancient simile, the self is like a river–let’s say the Mississippi. What we call ‘the Mississippi River’ is not an entity or a thing; it is only a name we give to a particular flow of water–to a process….. We mistake changing things for unchanging things. We assume because we have a name or concept for ‘the Mississippi River,’ the word and the idea must refer to some thing, when all it really designates is a flowing current, a movement, an activity. Well, our sense of personal identity is just like a river. Every part of what we include in our idea of ‘me’–every physical and mental component of the self–is changing, moment by moment. The kind of idea I have about ‘me’ deceives me. I think my concept of ‘me’ refers to a unitary, independent, and unchanging entity, when all it denominates is a flow.”

Very interesting and very Buddhist. I don’t know how this would work in a Christian mystical theology or metaphysics, but it does seem to me that one of the obstacles to a deep Christian mystical view of reality and our selfhood is the view of ourselves as these static fixed solid entities–like marbles in a jar, just rubbing against each other, and in a sense just rubbing against the reality of God.

So leaving behind this intriguing book, we now ask ourselves some more questions about this Nobody that we are. Who am I really? And why do we call this deep self “Nobody”? Because we can never “get hold” of our true deep self (but a zen master once grabbed a monk by his nose and shouted that he had found that monk’s true self) by counting it, numbering it, examining it–we will never see it in a mirror–never create a resume for it, never put it on exhibit, never put a label on it, a title, a name–it is truly nameless, etc., etc. It is not there as another object in the world of objects. And yet that true deep self is also not some exotic, special self, accessible only in special spiritual states. No it is always there when we wash the dishes, chop wood, offer a glass of water to someone, etc. Zen is very good at grasping this, but the Christian vision maybe has a sense of this to its very depths lost in the Mystery of God. I have often asserted in this blog how important it is to have a sense of the Absolute Mystery of God if we are going to have a serious spiritual life and have any inkling of our own identity. We are one with Christ in the depths of our being and so lost in that very Mystery. It is a great assertion of Catholic (and Orthodox) mystical theology that we “know” God best through a great and profound “unknowing”–that God is that fundamental and absolute Mystery. And so our very being in being lost in the depths of God through Christ enters into that same apophatic condition of “unknowability.” The “cloud of unknowing” surrounds not only God but the core of our being, our heart, our identity. There is no language that can express our “oneness with God,” and it is precisely that which is our identity. Thus, Nobody!

From a poem by Merton (“In Silence”):

Be still

Listen to the stones of the wall.

Be silent, they try

To speak your

Name.

Listen

To the living walls.

Who are you?

Who

Are you? Whose

Silence are you?

Who (be quiet)

Are you (as these stones

Are quiet). Do not

Think of what you are

Still less of

What you may one day be.

Rather

Be what you are (but what?) be

The unthinkable one

You do not know.

And, trust me, the PATH to that may best be described as No-way because that deep self is not there for any techniques or methods or practices to “discover”–not even meditation and prayer. There is no formula, no “puzzle” to solve, no “map,” no “how” to find this deep self–yet in the very next breath, there it is!

One last reflection. For those in the Christian tradition, the Gospels point at this deep hidden self in so many different ways, but the language and images and symbols get deflected into superficial directions. Consider a deeper, contemplative approach, like Merton’s little meditation on Luke’s Christmas narrative–you will find it in his little book of poems and reflections called Rain and the Rhinoceros–I forget the exact title of the meditation but I think it is taken right from Luke, “There was no room for them in the Inn.” Merton meditates on the Nativity narrative (starting at Luke 2:1): “In those days a decree went out from Emperor Augustus that all the world should be registered….” This is NOT a warm, fuzzy romantic scene with Santa and reindeer not far off and Christmas carols and eggnog. The Empire wants you numbered, counted, fixed with an identity that the Empire can recognize. The Empire is filled with this vast social movement where crowds are on the move. And “important people” are busy doing “important things”: “…while Quirinius was governor of Syria.” Mary and Joseph (and the child-to-be-born) do not stand “outside” this world; they are not ethereal beings; they too are to be counted and numbered; but as Mary is about to give birth to Jesus, they end up in a kind of cave–the word “manger” doesn’t really do justice to the setting–because “there was no room for them in the inn.” They get pushed around by the Empire for its own purposes, but their place is no-place; certainly not with the crowds that simply go along with the Empire in its “registering” everybody. When it’s time for the birth of the one who will reveal to us our own oneness with God and an identity that the Empire has no inkling of, the setting is one of being “outside” this vast commotion of the Empire. Luke really emphasizes that point in the next paragraph.

“There were shepherds living in the fields…” These are the consummate “outsiders”–like monks, or like monks should be. The shepherds are not part of the commotion and agitation of the Empire. They do not draw their identity from the Empire and so they “count for nothing.” To be sure they are “Nobodys”. They dwell in the night outside, not in the crowded inn or the crowded cities, but in the lonely fields, in the darkness, in silence, keeping watch…. They are the poor ones, the simple ones,… These are the only ones “qualified,” these are the only ones capable of bearing witness to the Mystery of God and the human being. They recognize the call to that No-place where that Divine Mystery emerges into Light; they respond. And this whole narrative is filled with a quiet joy which is certainly not the “exhilaration” of ego fulfillment. Rather it is the blessed joy of abiding always within this mystery.

A Blessed Christmas to all from this No-monk!