Let me begin with a poem written about a 150 years ago by a great Victorian poet and writer, Matthew Arnold. The poem is “Dover Beach,” one of his most famous poems, and this is how it goes:

The sea is calm tonight.

The tide is full, the moon lies fair

Upon the straits; on the French coast the light

Gleams and is gone; the cliffs of England stand,

Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay.

Come to the window, sweet is the night-air!

Only, from the long line of spray

Where the sea meets the moon-blanched land,

Listen! you hear the grating roar

Of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling,

At their return, up the high strand,

Begin, and cease, and then again begin,

With tremulous cadence slow, and bring

The eternal note of sadness in.

Sophocles long ago

Heard it on the Ægean, and it brought

Into his mind the turbid ebb and flow

Of human misery; we

Find also in the sound a thought,

Hearing it by this distant northern sea.

The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth’s shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furled.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,

Retreating, to the breath

Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear

And naked shingles of the world.

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

Various friends have pointed out on more than one occasion that I am too pessimistic in my outlook, but compared to Matthew Arnold in this poem I am practically a raving optimist! But on a serious note, the poem does have a sadness, a melancholy, a seeming hopelessness in its vision. And yet it is also strangely attractive, challenging whatever optimism we might bring to the table. And calling us to a higher reality than all our social arrangements, including those of religion.

The poem begins with the seeming tranquility and stability of an evening by the sea. It is a quiet ocean; there is a beauty in the moonlight on the waters, “the cliffs of England stand glimmering and vast,” hinting at both the beauty of Nature and the glory of the British Empire. We seem to be lulled into resting on this “foundation” of human life, but as the Gospel points out there are many “foundations” out there that are nothing more than sand and if you build your house on that you are doomed.

The poem then jolts us out of our reverie by deconstructing this seeming tranquility. The human situation, social, religious and natural, is just as vulnerable as the little pebbles to the turbulence of the waves that beat on the beach. It is a timeless situation, both ancient and modern humans had to deal with the “turbid ebb and flow of human misery.” What is implied in these lines is also a pessimism concerning so-called “progress” in human science and technology as our “hope” for the future. But neither is religion spared from this darkness. When Arnold refers to “the Sea of Faith,” he means formal religion, the Christian churches through the centuries. In the 19thCentury Europe it was all falling apart and shrinking into insignificance.

The poem ends in a remarkable way. Outside the human heart there is nothing, absolutely nothing that we can “build our house on,” that we can trust, that is a source of consolation, etc. “Ah, love, let us be true to one another!” Obviously a reference to an authentic love between a man and a woman, but this icon represents all that comes from an authentic pure heart. The “truth” there is all that we ultimately have, and when we lose sight of that as so much of humanity seems to do, then we sink to the depths and darkness of those last lines of the poem. Considering that this was written just a few decades before the start of the 20thCentury and World War I, truly Matthew Arnold was prescient. When we walk in that darkness, and darkness it is no matter how lit up it seems to be by our techno world, we discover the nihilism of Shakespeare’s Macbeth: “Life is a tale told by an idiot full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.”

I write all this because it seems that we are in a similar situation, where we may be sinking ever deeper into a morass of human confusion and darkness. If you think there is any solution to be found in the messages of politics, economics or religion–I cannot cease marveling how bad off the Catholic scene has become with the priest scandal being so much worse than even recently thought (and here I mean formal religion, not the truths within all the great religious traditions), I think you will at the very least be seriously disappointed, and maybe even become an agent of this darkness. Arnold’s insight is still our “true star” to guide us. Only that which is the truth that abides in our heart will matter in the long run. We must be “true” to one another, and this may entail a deep silence and solitude or it may entail a hidden self-sacrifice which no accounting can figure out. Whatever it be, it is only this which allows us a transcendent vision of our situation.

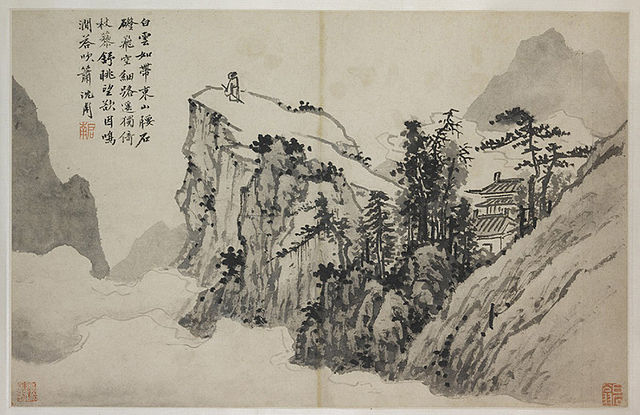

And this brings me to the next topic: Ikkyu. You may wonder what does Ikkyu, a medieval Japanese Zen monk and poet, have to do with these reflections. Well, first of all, he is one of my favorite people, so that is enough reason (!); but seriously he is strangely reassuring to me and a key reminder. Ikkyu is not some “figurine” in a meticulously manicured zen garden; he lives in a violent and tumultuous setting, he is beset with a decadent zen culture, and his own personal life has a good dose of chaos in it. He is a good reminder of how there is no ideal time or place for our own transformation, for our own life in God. Sometimes we romanticize certain times and places and religious arrangements and this itself can become a serious obstacle to our journey in depth. Yes, there are some places and some times that may be a bit better off, but rest assured this will not last and ultimately it cannot be the foundation on which we build our house. This is the meat of Arnold’s poem; the ebb and flow of human misery will always reassert itself.

So who is this Ikkyu? (His name translates as “having once paused”). His years are 1394 – 1481. His mother was a “lady-in-waiting” at the emperor’s court, and it appears his father was the emperor’s son. Mother and child were ousted from the palace because even a bastard son could make a claim to the throne. Ikkyu grew up in great poverty, but his mother managed to send him at age 5 to Ankoku-ji, a Zen temple in Kyoto. There he was well-trained in Buddhist scriptures and the classics of China and Japan. As a young boy he appears to be very bright and very playful, but his whole life he carried a sadness for the unjust treatment of his mother, who died in poverty. Another interesting thing is that in temple life homosexual love was prevalent…he was exposed to this quite early but he then turned “the other way.” To the very end of his 87 years he was totally fascinated by members of the opposite sex. In fact he often preferred staying in brothels rather than in monasteries. In this regard and in so many others he was a kind of “Zen fool,” when perhaps that was the only road open to integrity and truth.

At age 16 he left his temple and the established zen culture. He was seeking something much deeper than external zen credentials, which seems to have been the preoccupation of zen monks then (and perhaps now). And then this from an introduction to Ikkyu’s poetry, Having Once Paused: “Zen monasteries of the period functioned in ways reminiscent of the medieval European church. They were lavishly patronized, rich in land and peasant farmers, traders in luxury goods, repositories of culture and its accoutrements, and perfectly interpenetrated by the concerns of their political lords. These make a poor home for serious Zen practice, and Ikkyu’s home temple was no exception. At sixteen years old, he quit in disgust and for the next fifteen years trained in poverty under the two most exacting zen masters he could find.”

The first master he lived with was Ken’o, who was considered an eccentric who lived in a secluded hut outside Kyoto. This from Extraordinary Zen Masters: “Earlier in his life Ken’o had caused a stir when he refused to accept an inka, a certificate of enlightenment, from Muin,…. In those days such certificates–often purchased or fraudulently obtained –were essential for winning a position at a major temple. Thus, Ken’o act of rebellion excluded him from becoming a member of the Zen establishment–which suited him and his single disciple, the stubborn and determined Ikkyu, just fine.”

Ikkyu stayed with Ken’o until the latter’s death; then followed a period of mourning, loss, depression until his mother snapped him out of it and he joined another Zen master who was even more severe and “odd” than Ken’o. This was Kaso, who had gained enlightenment under Daio who had spent years deepening his realization while living as a beggar in the vicinity of Kyoto’s Fifth Avenue Bridge. So you can see that Ikkyu fitted in with a kind of “Zen fool” tradition of sorts!

Ikkyu had several zen realizations during his stay with Ken’o, but when the latter tried to present Ikkyu with an inka it first got thrown away, then torn up, then another copy burned by Ikkyu. His rebellion against the zen establishment was absolute and complete, but his devotion to Kaso was very real: “He was so devoted to Kaso that he cleaned up his master’s excrement with his bare hands when the ailing Kaso had diarrhea and soiled himself”(Extraordinary Zen Masters).

There are a lot of stories about Ikkyu, but we will just touch only on a couple. He grew quite famous, his reputation extraordinary and quite mixed to say the least. He was even invited to be an abbot on several occasions, even accepted, but gave up quickly in that endeavor.

From Extraordinary Zen Masters:

“When he was staying in Sakai one year, Ikkyu carried a wooden sword with him wherever he went. ‘Why do you do that,’ people asked. ‘Swords are for killing people and are hardly appropriate for a monk to carry.’ Ikkyu replied , ‘As long as this sword is in the scabbard, it looks like the real thing and people are impressed, but if it is drawn and revealed as only a wooden stick, it becomes a joke–this is how Buddhism is these days….’”

“Once a rich merchant invited a number of abbots and famous priests to a feast of vegetarian dishes. When Ikkyu showed up in his shabby robe and tattered straw hat, he was taken for a common beggar, sent around to the back, given a copper coin, and ordered to leave. The next time the merchant hosted a feast, Ikkyu attended in fancy vestments. Ikkyu removed the vestments and set them before the tray. ‘What are you doing?’ his host wanted to know. ‘The food belongs to the robes, not to me,’ Ikkyu said as he was going out the door.”

“The down-to-earth, no-nonsense Zen master had many run-ins with the yamabushi (ascetics who practiced austerities in the mountains to attain supernatural powers). Once a big, swarthy yamabushi accosted Ikkyu and demanded, ‘What is Buddhism?’ Ikkyu replied, ‘The truth within one’s heart.’ The yamabushi took out a razor-sharp dagger and pointed it at Ikkyu’s chest. ‘Well, then, let’s cut out yours and have a look.’ Without flinching, Ikkyu countered with a poem:

Slice open the

Cherry trees of Yoshino

And where will you find

The blossoms

That appear spring after spring?”

The stories go on, but I want to conclude with a more touching episode. Ikkyu was a complex figure to say the least, not someone to imitate but certainly someone who inspires some of us in “such times as these,” and furthermore he vividly illustrates Arnold’s call to “stay true to one another.” In his old age, in his seventies, Ikkyu fell in love with a woman in her thirties who was a blind musician. She lived with him until his death at age 87. There was a peace, a serenity, a fulfillment in his old age that surpasses all usual understanding.