We will have a respite from my historical journey through Zen Buddhism this time—just a few odd pieces that have come to my attention.

There are two “happy” documents to come out from the recent gathering of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (to be distinguished from the more conservative Missouri Synod). There’s probably a lot more good stuff going on there, but it’s these two that caught my attention. First of all there was a “declaration of unity” with the Roman Catholic Church. It admits that there still are some real issues that need addressing but a “basic unity” is there and is more a process that we all are involved in. (By the way, Pope Francis is going to Lund, Sweden in October to participate in a celebration of the Protestant Reformation.) I always thought a lot of the Protestant-Catholic disputes were just so much verbiage due to ill feelings on both sides, gross misunderstandings in all the words we “shouted” at each other, and definitely some decadence and arrogance on the Catholic side. When we calmly look at what we hold and believe in, then the differences do not go away but do seem to shrink.

The other Lutheran document was a simple one declaring the church’s support of the Palestinian people and condemning the Israeli practice of “apartheid” and the grabbing of their land. It is a courageous stand considering the powerful Israeli lobby in this country, but it is also in keeping with the sentiments of quite a few other religious groups. I am happy for all my Lutheran friends, but I do wish their church would get a bit more “mystical”!! (Not that mine is much better!)

Recently I again came across a well-known quote by Merton but one whose full ramifications are hardly explored. Here is the quote: “What can we gain by sailing to the moon if we are not able to cross the abyss that separates us from ourselves.” The fact is that we are trying to cross that abyss in all we do, try to do, in all our efforts and actions. This universal condition is explained in Catholic theology in terms of what is called “original sin.” But theology never gets to the nitty-gritty of what this really means in everyday life except in abstract words like “sin,” “greed,” “lust,” etc. And it readily loses the fact that religion itself shares in this problem. In other words religion itself can easily be part of the problem and not just part of the solution.

Now Buddhism, for one, has a more existential word: “suffering”–that which is that deep dissatisfaction in pursuit of this self that we feel is “graspable” in or through some experience out there; something that frees us from that spiritual vertigo of that abyss as deluded we imagine ourselves having crossed it. Modern life is so good at that. Visualize those racing greyhounds chasing a virtual rabbit, round and round they go, and never do they catch it. Such is a good picture of what is going on in all seeking of power and wealth and status and name and adulation and fame and possessions and yes of course the continual play of sex; you see this pursuit in endless shopping of something “ever new,” some gimmick to give a temporary relief from the anxiety of sensing that abyss within ourselves, of sensing that we are not really “ourselves” but some image. Here we can also find religion as this kind of “gimmick”–an infantile religion that keeps us in an infantile place.

Zen is really good at addressing this problem; and here I don’t mean just Zen Buddhism, but the heart of it all which is really Zen and which is at the heart of all true mysticism (this last statement I admit can be argued). All those good old Zen masters in China and Japan, all their words and gestures, everything they did and were, all this simply pointed at the “overcoming” of that abyss, at the full realization of selfhood, at the resolution of what seems like an unbridgeable duality. Now as I said all authentic religious mysticism deals with this also, but it’s not just religion that’s seeking an answer here. In the 1950s it became apparent that psychoanalysis was a secular version of an indepth analysis that dealt with this problem. At least this seemed the case with some great figures like Erich Fromm, who not only was open to religious language but also engaged in dialogue with Zen and religion through figures like D.T. Suzuki and Thomas Merton.

In 1957 Erich Fromm organized a conference around the topic of Zen and psychoanalysis. A number of practitioners came, such as Richard De Martino who was a psychoanalyst and a student of Zen and whom I found very illuminating, and of course D. T. Suzuki. Here is a summary of some things that Fromm had to say:

“At the beginning of the century, people coming to psychoanalysis were mainly those suffering from symptoms (i.e. paralyzed limbs, obsessional thoughts and actions). Now the majority of patients are those suffering from an “inner deadness”; they are generally unhappy with their lives wherein success has lost its satisfaction. This inner deadness manifests in the individual as an alienation from self, others and nature. Life poses the question – “how can we overcome the suffering, the imprisonment, the shame which the experience of separateness creates; how can we find union within ourselves, with our fellow man, with nature?” One is driven to solve this Koan – even in insanity an answer is given by striking out the reality outside of ourselves, living completely within the shell of ourselves and thus overcoming the fright of separateness, or alienation. The answers are only two: to find unity through regression to the pre-awareness state; or to be fully born, to develop one’s awareness, one’s reason, one’s capacity to live, to such a point that one transcends one’s own egocentric involvement, and arrives at a new harmony or oneness with the world. …. Well-being is possible only to the degree to which one has overcome one’s narcissism, and is open, responsive, sensitive, awake, empty (in the Zen sense), fully related to others and to nature affectively; to become what one potentially is; to have the full capacity for joy and for sadness; to be creative (of seeing the world as it is and experiencing it as my world, the world created and transformed by my creative grasp of it – so that the world ceases to be a strange world ‘over there’ and becomes MY world; to drop one’s Ego, to give up greed, to be and to experience oneself in the act of being, not in having, preserving, coveting, using. Most of what is in our consciousness is “false consciousness” and it is essentially society that fills us with these fictitious and unreal notions. This ‘social filter’ permits certain experiences to be filtered through to our awareness, while others are stopped and held in the unconscious, e.g. not allowing the awareness of a subtle or complex experience (seeing a rosebud in the early morning, a drop of dew on it, while the air is still chilly, the sun coming up, a bird singing) because the social filter does not consider such a multi-sense experience as sufficiently ‘important’ or ‘eventful’ to be recognized.

Again, certain cultures do not form words or vocabulary to recognize perspectives of reality not seen as priority distinctions. Different cultures have varied logic processes, and the logic of a reality can only be perceived through one’s cultural social filter. The filter of one’s culture may not allow one to be aware of certain attitudes or inclinations taboo to the group. The reason behind the social filter is that any society, in order to survive, must mold the character of its members in such a way that they want to do what they have to do; their social function must become internalized and transformed into something they feel driven to do, rather than something they are obliged to do. Were the society to lose its coherence and firmness, many individuals would cease to act the way they are expected to, and society itself would be endangered. In all societies there are taboos, the violation of which results in ostracism. The individual, cravenly fearful of ostracism, cannot permit himself to be aware of thoughts or feelings inconsistent with his culture, and learns to repress them.

Consciousness represents ‘social’ man, the accidental limitations set by the historical situation into which an individual is thrown. Unconsciousness represents universal man, the whole man, rooted in the Cosmos; it represents the plant in man, the animal in him, the spirit in him; it represents his past down to the dawn of human existence, and it represents his future to the day when man will have become fully human, and when nature will be humanized as man will be naturized. By repressing reality through the distorting cultural social filter, we “see as through a glass darkly (I Corinthians 13:11). Again, via cerebration we see the experiences as being, if not distorted, unreal – e.g. I believe I see – but I only see words; I believe I feel, but I only think feelings. The cerebrated person is the alienated person, the person in the cave (Plato) who sees only shadows and mistakes them for immediate reality. This cerebrated alienation arises through the ambiguity of language. In using words, people think they are transmitting the full experience. The receiver thinks he sees the transmitted message, inasmuch as he employs his own personal meaning of the words – he thinks he feels it – yet for him, the receiver, there is no personal experience except that of his own memory and thought. When he thinks he grasps reality, it is only his brain-self that grasps it, while he, the whole man (eyes, hands, heart, belly) grasps nothing – in fact, he is not participating in the experience which he believes is his.”

(The extended quote above is from notes on the conference that I found on the internet. I believe these are summaries of Fromm’s talk.)

And here is a direct quote from Fromm during this conference:

““Well-being is the state of having arrived at the full development of reason: reason not in the sense of a merely intellectual judgment, but in that of grasping truth by “letting things be” (to use Heidegger’s term) as they are. Well-being is possible only to the degree to which one has overcome one’s narcissism; to the degree to which one is open, responsive, sensitive, awake, empty (in the Zen sense). Well-being means to be fully related to man and nature affectively, to overcome separateness and alienation, to arrive at the experience of oneness with all that exists—and yet to experience myself at the same time as the separate entity I am, as the individual. Well-being means to be fully born, to become what one potentially is; it means to have the full capacity for joy and for sadness or, to put it still differently, to awake from the half-slumber the average man lives in, and to be fully awake. If it is all that, it means also to be creative; that is, to react and to respond to myself, to others, to everything that exists—to react and to respond as the real, total man I am to the reality of everybody and everything as he or it is. In this act of true response lies the area of creativity, of seeing the world as it is and experiencing it as my world, the world created and transformed by my creative grasp of it, so that the world ceases to be a strange world “over there” and becomes my world. Well-being means, finally, to drop one’s Ego, to give up greed, to cease chasing after the preservation and the aggrandizement of the Ego, to be and to experience one’s self in the act of being, not in having, preserving, coveting, using.”

Now psychotherapy has had a lot of criticism and many key critics and much of this is well-deserved, but in the hands of a specially gifted practitioner like Erich Fromm it becomes an acute tool to diagnose what ails us, not in theological language but in existential terms. Thomas Merton himself benefited from his encounter with Fromm and his kind of psychotherapy. Then there was also Merton’s famous exchange with the Iranian Sufi who was a psychotherapist, Reza Aratesh. Merton wrote a whole essay about his work, and that can be found in the collection Contemplation in a World of Action.

Recently I came upon this Zen story that pertains to one of the lesser-known Zen masters of China, Lung-t’an.

“A nun asked Lung-t’an as to what she should do in order to become a monk in the next life. The master asked, ‘How long have you been a nun?’ The nun said, ‘My question is whether there will be any day when I shall be a monk.’ ‘What are you now?’ asked the master. To this the nun answered, ‘In the present life I am a nun. How can anyone fail to know this?’ Lung-t’an fired back: ‘Who knows you?’”

A truly remarkable encounter! The nun boldly addresses her condition on a social/historical level, and the zen master takes to a wholly different level. You can hear the complaint in her voice about the inherent unfairness of her status as a woman–nuns are rated inferior to monks. She is quite right as far as that goes, and this is the historical predicament of all women in all the religious traditions. But she is a kind of proto-feminist and she raises her voice with this master. No passive “little flower” here! But the Zen master takes her to a completely other level of identity. She brings her problem, her pain, her anxiety, her disenchantment, her impatience, her sense of justice; and Zen simply uses all that for leverage to open up a whole new vista of who she is. Zen does NOT solve our “problems”; it uses them to open us up to an awakening to whom we really are. And from this will spring the needed creativity and resources that will allow us to deal with our problem.

(Recall St. Paul’s: There is no more male or female, no slave or free, no rich or poor, no Jew or Gentile….all these identity markers which were so important in Paul’s world are now radically relativized–slavery is NOT by the way justified as some folk seem to think by this kind of language–and a whole new identity reality is pointed at which Paul equates with “Christ.” That is the primary reality, and once you awake to that, then you can deal with all these other problems and divisions according to your new sense of identity.)

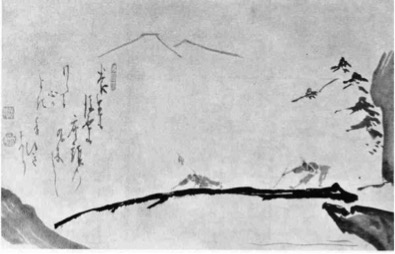

And to conclude I just want to share this image: a drawing by Japanese Zen Master Hakuin, 18th Century. The title of this drawing is “Blind Men Crossing a Bridge.” An apt portrayal of the spiritual journey!!