So now we come to Part IV, my favorite part and perhaps the most difficult to grasp. Here Abhishiktananda steps off the “well-beaten path” and steps out over “the Great Abyss” with no “safety nets” in sight! Again and again he is unrelenting in his focus on the Beyond, and to such a degree that no institution, whether religious or cultural, can possibly contain what he says.

Abhishiktananda begins by blasting any notion of sannyasa other than as a dynamic related to a most profound inner experience: “It is precisely the all-transcending character of sannyasa that makes some people vehemently deny the possibility of its existing as an institution within the framework of any social or religious order…. Sannyasa is an inner experience–just that. The sannyasi is the man whom the Spirit has made ‘alone’, ekaki. Any attempt to group sannyasis together, so that they may be counted or included in a special class, is a denial of what sannyasa really is. The sannyasi is unique, each individual sannyasi is unique, unique as the atman is unique, beyond any kind of otherness, he is ekarsi, since ‘no one is different from or other than myself.’ The sannyasi has no place, no loka. His only loka is the atmaloka, but this is both a-loka (without loka) and sarva-loka (in all lokas). He cannot enter into dvandva (duality) with anything whatever–so, if there is a class of sannyasis, it is all up with sannyasa!”

He is especially acerbic with any idea or view of sannyasa as a “belonging to some group” or as constituted by any external measures or signs, etc.: “They have renounced the world–splendid! So from then on they belong to the loka, the ‘world’, of those who have renounced the world! They constitute themselves a new kind of society, an ‘in-group’ of their own, a spiritual elite apart from the common man, and charged with instructing him, very like those ‘scribes and pharisees’ whose attitude made even Jesus, the compassionate one, lose his temper. Then a whole new code of correct behavior develops, worse than that of the world, with its courtesy titles, respectful greetings, orders of precedence and the rest. The wearing of saffron becomes the sign, not so much of renunciation, as of belonging to the ‘order of swamis.’” Here he is describing mostly the situation in India, but it is clear that this description sadly fits way too many within western monasticism and religious life.

So sannyasa is first and foremost related to a deep and profound spiritual experience which manifests itself as “renunciation”–and this was already alluded to in Part I. Sannyasa is afterall a life of renunciation as we said, but this renouncement has to cut very, very deep or else we are merely playing at it. Abhishiktananda: “At the beginning of his diksa the one who is taking sannyasa repeats this mantra: ‘OM bhur bhuvab svab samnyastam maya’–‘All the worlds are renounced by me.’ But so long as there remains a ‘by me’ (maya) in the one who is renouncing the world, he has not yet renounced anything at all! The maya (I, me) is annihilated, blown to pieces, when the renunciation is genuine; and the only genuine renunciation is a total one, that is, when the renouncer is himself included in the renunciation. Then ‘maya’ is wiped out, renunciation is wiped out, and so is the renouncer. Then the heavens are torn open, as happened at the baptism of Jesus, and the truth of advaita shines out, needing no words, names or expressions, being beyond all expression. Words are quite incapable of expressing the mystery of that truth which pierces through to the unfathomable abyss of the inner experience, beyond the I/Thou, Father/Son, of Jesus’ baptismal initiation, beyond the tattvamasi/ahambrahmasmi (That art thou/I am Brahman) of the Upanishadic initiation, beyond all sannyasa, beyond all light that can be seen or spoken of, beyond any ‘desert’ that is still known as such.”

This is the core message of Part IV. The “renouncer” and the “renouncing” have to go also! Otherwise the would-be monk/sannyasi pats himself on the back that he is such a “renouncer.” It is interesting to note here that the reality of this kind of ultimate renouncing cannot be a “selfie” to put it in current lingo–it cannot be a do-it-yourself project. And here both John of the Cross and the Upanishads agree–it is only the Divine Activity within one that can do this. Abhishiktananda: “That can only be done when the tejobindu, the ‘pearl of glory’, the self-luminous one of which the Upanishads speak, flashes forth, the ray of light that illuminates the depth of the soul.”

Of course when we speak of “inner experience,” there is always the danger of self-delusion or of simply being “swept off one’s feet” by some psychic phenomenon. In some ways this is a trivial problem because the “nitty-gritty” of life will bring one back to earth very fast; but there is a special problem for those who live in intense spiritual environments, like monasteries, where they can talk themselves into thinking they have these “special experiences” and then they dress them up with quotes from scripture and spiritual writings and this begins to pass for “what they are there for.” They look for “signs” of realization, and truly they do find these “signs.” This kind of thing takes place in all and various religious groups where some individuals will “claim” ultimate realization because they “feel” it. Obviously this has nothing to do with sannyasa. Abhishiktananda: “However, as long as the light has not shone fully within, and the tejobindu–that pearl of glory in the depth of our being–has not yet totally transformed the buddhi (discriminating faculty) to its ultimate recesses, one has no right to pronounce the mahavakya: aham Brahma asmi ( I am Brahman). The ‘aham’ of which he is aware in his outer consciousness is still essentially the ego of the one who utters the formula, and only very indirectly does it point to the deep aham to which the Scriptures refer.”

Neither this profound inner experience, nor true sannyasa is “built upon” or dependent on anything else or needing any support. I am reminded of the questions raised pertaining to Jesus: By whose authority does he say what he says, by whose authority does he do what he does? Indeed, a would-be sannyasi might claim some external authority for his “sannyasa.” By whose authority is he a sannyasi? By the authority of scriptures? By the authority of a guru with all the paraphernalia of sannyasa? By the authority of a religious institution? By the authority of a claimed inner experience? Abhishiktananda’s position is so radical that in fact there is no authority for this Reality except the Reality itself, the Spirit if you will in Christian terms, the experience of advaita–but even here you want to be very careful what this term really means. True sannyasa is beyond all signs, all foundations, all authorities. Abhishiktananda: “The atman, the Self, rests on itself alone. To try to provide it with a would-b e ‘support’ outside itself amounts to letting the sand slip through one’s fingers. The same can be said of sannyasa, the supreme renunciation. As long as we try to find a support (pratistha) for it in anything else–say, a mantra, a diksa, a tradition, a vamsa–we simply miss the point. Anyone who relies on such things in order to gain recognition and acceptance in society…has not yet understood…. His true support is not here. It is nothing that can be shown, dated, described, proved by witnesses (such as the guru or abbot who gave him diksa)…. No revelation, no ecstasy, no Scripture, no man, no event, no diksa, nothing whatever can be his support….”

At this point in his essay, Abhishiktananda gives us what I consider his most beautiful, most profound and most important quote: “In the heart of every man there is something–a drive?–which is already there when he is born and will haunt him unremittingly until his last breath. It is a mystery which encompasses him on every side, but one which none of his faculties can ever attain to, or still less lay hold of. It cannot be located in anything that can be seen, heard, touched or known in this world. There is no sign for it–not even the would-be transcendent sign of sannyasa. It is a bursting asunder at the very heart of being, something utterly unbearable. But nevertheless this is the price of finding the treasure that is without name or form or sign…. It is the unique splendour of the Self–but no one is left in its presence to exclaim, ‘How beautiful it is!’”

I am not going to comment on this passage—it would take many pages just to begin to point out its significance and its many incredibly deep insights. But I would like to add just a few reflections. First of all, Abhishiktananda’s thought here resonates with some Rahnerian themes–the theology of Karl Rahner is not far off here, but it also must be said that Abhishiktananda seems to express something from a very deep experience beyond the ken of most theologians–even Rahner–not that this great theologian was not a man of the Spirit and of spiritual experience. Secondly, if we truly grasped the insights buried in these words, it would revolutionize the way we look at each other, at other human beings, at religious life, at the spiritual life…. His words open to us a vision encompassing all human beings, whether in a family, or active religious or monastics/sannyasis–it really doesn’t matter–all life is oriented toward this Transcendent Reality, and the sannyasi is only there to remind us of that fact. But the sannyasi’s “transparency” is truly effective only when the sannyasi is “no more”!!! Very hard to do– to say the least! This probably makes no sense to a lot of people. How do you pass through the “eye of THAT needle”?!–we are all so “rich” in ego-self. Jesus says that only God can accomplish this, and the Upanishads are really not that far off in this regard. In fact even if we spend our lives in the pursuit of wealth, sex, power, or we just meander through the trivial pursuits of our consumer culture, in the end we die and we are pulled “through the eye of that needle” and nothing is left except that which the sannyasi is pointing to–but this is Unspeakable and One with God.

So Abhishiktananda continues in this vein: “It is an invisible ray issuing from the Pearl of Light, the tejobindu, in the deepest abyss of the Self; it is also a death-ray, ruthlessly destroying all that comes in its way. Blessed death! It pierces irresistibly through and through, and all desires are consumed, even the supreme and ultimate desire, the desire for non-desire, the desire for renunciation itself. As long as any desire remains, there is no real sannyasa and the desire for sannyasa is itself the negation of sannyasa. The only true sannyasi is the one who has renounced both renunciation and non-renunciation. Farewell then to any recognition by others that I am a sannyasi.” So in this “impossible” description one can hear echoes of Buddhism. For many this will seem like merely playing with words and impossible to make any sense of this. But it is like a Zen koan, not a logical argument. In fact one could say that this sannyasi that Abhishiktananda describes is truly an embodied koan “in the flesh.” One does not arrive at this life through a process of logical thinking–or even cultural or religious processes.

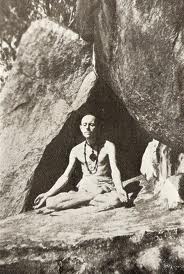

So Abhishiktananda continues: “The kesi does not regard himself as a sannyasi. There is no world, no loka, in which he belongs…. Wherever he goes, he goes maddened with his own rapture, intoxicated with the unique Self. Friend of all and fearing none, he bears the Fire, he bears the Light. Some take him for a common beggar, some for a madman, a few for a sage. To him it is all one…. His support is in himself, that is to say, in the Spirit from whom he is not ‘other.’”

As I mentioned earlier, Abhishiktananda will soften this radicalism in Part V where he brings back the symbolic, and one might say “theological,” significance of the diksa, the initiation into formal sannyasa. One might accuse him of “having his cake and eating it too”–of being self-contradictory…but he is reaching realms where only the language of paradox is even allowed to approach. What’s important to realize and what’s very obvious is that true sannyasa for Abhishiktananda is never simply the equivalent of formal sannyasa into which one is initiated in a sacramental way. This has its own significance as we shall see, but now Abhishiktananda has an intense focus on what one might call “true sannyasa” or “the essence of sannyasa”–that which is connected to and expressive of an absolutely transcendent inner reality which no words or symbols can in any way touch. Whatever be our “formal” status, it is precisely this that ALL of us are oriented to whether we realize it or not. And now I get the import of that Merton axiom: monks are not “special people” but only what all people should be. Indeed, all monks and all sannyasis precisely serve that purpose when they are truly living out their lives. In any case, we will get into that in the next posting. Meanwhile let us conclude with the unrelenting radical message of this part of the essay: “From the call of the Spirit there is no release. Nothing can continue to have meaning or value for the man on whom the Spirit has descended. He no longer has either a past or a future. All plans made by him or for him, even the loftiest religious projects, are swept away like leaves before the wind…. Awakening must not be confused with any particular human or religious situation, with any specific state of life, or loka, or with any condition (or conditioning) which sets one apart. Even Gautama the Buddha seems to have tied the possibility of awakening too closely to the monastic life, and too often Hindu dharma has thought on the same lines.”

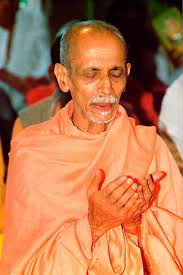

And: “’Self-realization’ is the great myth [my note:myth in the Jungian sense] of the Vedanta. When Sri Ramana says that the final obstacle to realization is the very idea that one ought to strive after it, he is in fact setting forth the definitive purification of the Spirit, that which sets man free and cuts the last ‘knot of the heart’…. It is the equivalent of the ‘dark night of the soul’ according to John of the Cross, who teaches that the ultimate act of union and perfect love is an act so spiritual that nothing in our created nature is able to feel it or lay hold of it, to understand or express it. It happens without our mind being aware of it or being able to apprehend it. Yet something in us knows that ‘It is,’ ‘asti.’ Both of these great seers refuse to allow that the final perfection, the awakening, has anything to do with space or time, or even thought. It is utterly mistaken to try to attain to some ultimate experience, as a result of which one might hold oneself to be a ‘realized man.’”

Amen! To be continued….