Old

Old age is not in favor in our society and culture. It is amazing how much effort and energy is spent in trying not to appear old. It is quite an industry. But it’s not just appearance that is at stake; old age is no longer considered an abode of wisdom and a deepened sense of life, but merely a time of “retirement,” whatever that means. So you spend your life “making money,” “doing,” “making something of yourself,” and then you quit and “play” in some socially acceptable old age activities. But what if old age is for bringing your whole life into focus, deepening your vision, growing in wisdom, assessing your “wrong turns” in tranquility, coming to terms with your own limits and blindness, understanding the nature of your “wounds,” reconciling with all that needs reconciling….and most of all understanding that your little self is not some castle or fortress that you need to protect and defend and manipulate for the much-advertised “successful life.” In other words, old age may be quite an “active” period but perhaps not in the way our society deems “action.”

Yes, what if old age brings about an enhancement of one’s intellectual, sophianic and spiritual vision. Perhaps it is only then that you peak in this regard. Perhaps it is only then that your most radical journey begins.

Speaking of which, let us divert momentarily to one of my secret loves: hiking and the people I admire, long-distance hikers. Not too long ago the magazine Backpacker featured a brief portrayal of some elderly long-distance hikers who are true legends. Here’s a few that are my favorites: (the accounts are right out of Backpacker)

Billy Goat

Image by NPS/Deby Dixon via Flickr

“I’m not on vacation. I’m not out for a weekend,” Billy Goat once told the Los Angeles Times. “This is where I live.” The former Maine railroad worker spends six months of every year hiking the Pacific Crest Trail. He’s now in his late 70s and still on trail as of the 2015 season. The triple-crowner has logged over 32,000 miles and has become a legend among long-distance hikers. To streamline the tedious process of signing his name in trail registers, Billy Goat inks a rubber stamp and leaves his red goat insignia in trail registers.

And then there’s: Emma “Grandma” Gatewood

Footwear: Keds sneakers. Shelter: shower curtain. Pack: a sack slung over one shoulder. Emma Gatewood is proof that family responsibilities don’t have to sideline long trail dreams. The mother of ultralight backpacking was also a mother of 11 and grandmother of 23. In 1960, she became the first woman to complete a thru hike, and at age 67, no less. She finished the trail for a second time two years later. Her toughness was beyond question. “Most people are pantywaists,” she allegedly once told Ray Jardine.

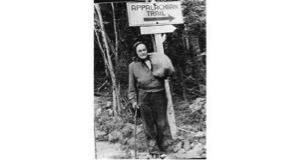

Another one: Lee “Easy One” Barry

Easy One started hiking the Appalachain Trail just a year after its official opening in 1937. In 2004, he set the thru-hiker age record: 81 proud years summiting Katahdin. He averaged 10 miles a day for the 220-day hike, a pace that hit the sweet spot for Barry. “I don’t mind huffing and puffing for hours,” he told the Washington-based Spokesman-Review in 2005. “I just want to be out here for the fun of it.”

One more:

Bill Irwin

Lost youth wasn’t the only obstacle beleaguering Bill Irwin: the 50-year-old thru-hiker was also blind. In 1990, he undertook the trail with kneepads and a guide dog, Orient, in lieu of map and compass. Together, the duo became known as the “Orient Express.” The eight-month trip was anything but smooth, but despite innumerable falls, cracked ribs, and a bout with hypothermia, Irwin became the first blind thru-hiker. He credits his faith for his perseverance as well as his motivation for getting the former alcoholic outdoors in the first place. “The first clear-eyed thing I had ever done was as a blind man, when I asked God to take charge of my life,” he wrote in Guideposts. “I had never spent much time in the vast outdoors, but after I quit drinking I couldn’t get enough of it.”

And finally:

Nan Drag’n Fly Reisinger

Drag’n Fly holds the record for the oldest woman ever to thru hike the Appalachain Trail. She reached the trail’s northern terminus in 2014 at age 74, alongside her friend, Carolyn “Freckles” Banjak, who was in her late 60s herself. The white-haired and red-headed duo referred to themselves as Fire and Ice. Their secret? Slow and steady wins the race. “I had to keep at it. I couldn’t take time off,” Reisinger told The Sentinel newspaper. “We had to hike every day and not take breaks.” Reisinger also credits good health, previous experience (she’s logged over 6,000 miles on the AT alone), and an active lifestyle complete with canoeing, gardening, and tap dancing.

These are amazing people in their own right, but for me right now they symbolize and hint at some very important insights concerning the spiritual journey. There is no “retirement” from this journey; the effort and “work” might only then begin in fact, whereas before one was only “prepping” for this. It’s interesting that in a culture like India the traditional religious journey involves the whole person in the various stages of life: first you are a “student,” a “learner”; then you are a “householder,” a married person with a family; finally you leave all this behind and take up the life of renunciation, devoting the whole of the rest of your life to spiritual deepening. Now of course few Hindus really follow this program anymore; the young are less and less seeing their lives moving toward a deep renunciation, more likely toward a more comfortable life!! Also, it is important to note that one can jump into this spiritual path of renunciation and total focus at any time in one’s life, it’s just that there is this amazing awareness that old age is a kind of ripening moment when one’s inner psychic energy is most attuned and less distracted for spiritual deepening. Perhaps it is only when you are older that you truly begin to appreciate the spiritual journey for what it is–before, in youth and middle age, there is always the temptation to get mesmerized by what society offers. True, there are many people everywhere who are attracted to some aspect of the spiritual life when they are younger, and there is much to be said for youthful energy and acuity of intellect; but the testing ground of true spirituality is always in old age–the fake, the delusionary, the vacuous, the transient, etc., all fall way and not much might remain but what is there will be a bit more real than what you started out with. True, old age in itself is no guarantee of any authenticity or truth or depth; the sad fact is that many people simply collapse into their lifelong blindness and succumb to a kind of lethargy of the spirit, thinking that their lives and their “journey” is ending. That’s why I consider these elderly long-distance hikers marvelous exemplars of the spirit needed as we journey into the Ultimate Reality and our true identity.